Over a century ago, Marcel Proust (1871-1922) described the French protagonist in his novel À la recherche du temps perdu (first translated into English as Remembrance of Things Past, but now commonly referred to as In Search of Lost Time) dipping a Madeleine in a cup of tea and having aroma-triggered flashbacks to his youth.

Experiencing a “Proustian moment” refers to the phenomenon of having a particular scent conjure up vivid memories of a specific time or place from one’s past.

As Cretian van Campen explains in the abstract for his non-fiction book, The Proust Effect: The Senses as Doorways to Lost Memories:

“[This effect] refers to the vivid reliving of events from the past through sensory stimuli. Many of us are familiar with those special moments when you are taken by surprise by a tiny sensory stimulus (e.g., the scent of your mother’s soap) that evokes an intense and emotional memory of an episode from your childhood.”

Olfaction research

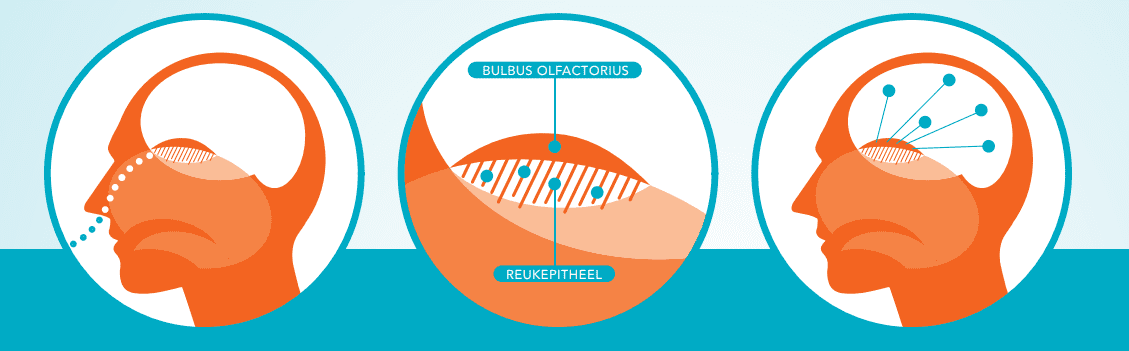

How do these vivid “Proustian” memories from early stages of childhood development get permanently etched into our brains? A new olfaction-based study (Aihara et al., 2021) in mice by researchers from Kyushu University offers some fresh clues. These open-access findings were recently published in the journal Cell Reports.

The Kyushu University researchers investigated mouse olfactory neurons and identified how the protein BMPR-2 regulates the selective stabilization of neuron branching by strengthening neural connections associated with a specific smell during early development.

The complex way that BMPR-2 “gates activity-dependent stabilization of primary dendrites during mitral cell remodeling” is a multi-faceted process that involves a protein called LIMK and glutamic acid neurotransmitters. For details on how this all works, check out the paper’s open-access Results.